Discipline ‘key to success in trading’

Last week, I was interviewed by Teh Shi Ning, one of the reporters from the Business Times, to share my trading journey and his success story.

“Having spent over 7 years in the markets, and spending at least 5 hours a day to practice, I am glad that I am able to pursue my dream as full time proprietary trader. Hopefully, after sharing my experiences, you will get a better idea of what trading is about, and do away with the misconception that it is simply risky gambling.”

Q: What got you interested in investing?

A: I actually got interested during my army days. My first foray was into options trading, where I blew my first account, but that got me hooked. My family is quite frugal and my parents advocate saving and investing prudently so they take a more long-term and passive approach to investing, such as dollar-cost averaging or buying unit trusts. Hence it was no surprise they were not very supportive of my trading. I built up my portfolio using my own capital and savings, and I worked as a financial planner after my national service. There, I learnt more about personal finance and investments. During this time, I also read widely and voraciously to stock up my knowledge database. When I went to university (SMU), I joined the investment club where I met many other enthusiastic traders. Eventually, I became the head of research and started teaching the classes.

Q: What’s your motivation?

A: Besides the obvious reasons like financial abundance and freedom (of time), I would say the main reason is that I cannot resist a good challenge. I used to be a national chess player in my younger days, and trading reminds me a lot of it, since it is an intellectual challenge that requires great mental discipline. Trading is challenging because of the discipline to wait and stay out till an opportunity comes, and then having the confidence to execute without hesitation, and most importantly mental grit to cut losses. But it’s also boring because 95% of the time is just spent waiting and observing.

Q: What’s your risk appetite like?

A: Risk is actually a very debatable concept. It really depends on what your definition of risk is. On one hand, I am a risk-taker because trading futures is conventionally deemed risky. On the other hand, my risk appetite is low because I am willing to let go of sub-optimal set-ups and only wait for the best opportunities before I place a trade. In addition, because I do not hold my positions for long periods of time, I am able to reduce the volatility and risk. To a trader risk management is very important, such as calculating optimal capital allocation, minimising drawdowns, and being aware of net exposure.

Q: How would you describe your trading style?

A: My style is largely inspired by market legends such as Jesse Livermore and Richard Wyckoff, and I specialize in price action and psychology. I aim to consistently seek out high-probability and low-risk setups, varying my strategy according to the different market scenarios and being aware of price catalysts. I also apply multiple timeframes, to enter the market when there are weak fluctuations against the main trend. Getting the timing right is the crux, and this comes with experience and gut feel.

Q: Any tips to share?

A: It is crucial to start investing or trading only when you have a sound strategy and methodology for analysis, taking into account your personal finances, risk profile and time horizon. As a new trader, do not be impatient. Take your time to master the skills and knowledge, and apply it slowly to gain experience, keeping your expectations on returns realistic. Once you understand the psychology and principles behind trading and apply them, you will start evolving as a trader.

Q: What other interests do you have besides trading?

Beside trading, my other great passion is tennis, and I find that there are quite some similarities between these two art forms. Yes, trading is also an art. In both games, consistency is the key to success. Take the tennis serve and strokes for example. Anyone can get lucky and hit a few power shots, but that does not make him a good player. Just the same a few windfall trades does’t make one a good trader. The idea is to be able to perform consistently over the long-run. To be able to do so takes a lot of discipline and practice.

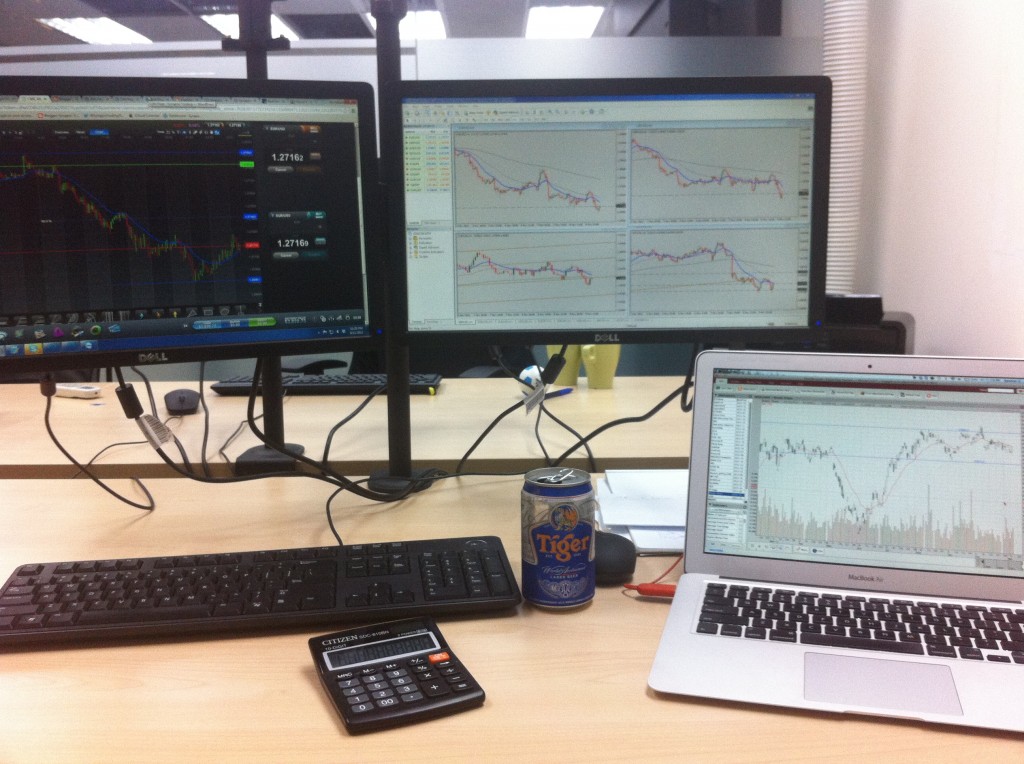

My other hobby is travelling, and trading is the perfect job because it allows me the freedom to travel whenever I want, and I can trade from anywhere as long there is an internet connection. In addition, trading also allows me to blend knowledge across different disciplines, and understand what goes on around the world.