It is easy to see why retail traders find indicators appealing because of their ease of use and clear-cut signals. In fact, many new traders think they know all about trading because they have learnt a few basic indicators that generate simplistic buy/sell signals. This kind of thinking is dangerous because it shuts them off from learning real trading skills like price action and behavioral analysis.

Table of Contents

What are indicators and how are they derived?

There are only five pieces of information we can get from charts: the open, high, low, close and volume. A skilled trader can interpret this in terms of market behaviour of psychology instead of processing it as a bunch of numbers. Indicators, on the other hand, attempt to use shortcut calculations to give meaning to these numbers. As a result, they can never be faster than reading the actual raw data. Manipulating data may also mask its information quality and granularity, causing you to miss out essential essential details.

Do professionals use them?

The answer is minimally. If you go to any bank/fund or professional trading arcade, and observe the traders who trade there, you will notice that their charts are mostly blank. This is not coincidence, because such a chart setup is optimised for reading price action, with as little distractions as possible. If you don’t believe me, go check it out yourself. As said by the famous Leonardo Da Vinci, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

The dangers of using indicators without real trading skills

Many traders, especially beginners, are drawn to indicators, hoping that an indicator will show them when to enter a trade. what they don’t realise it that the vast majority of indicators are based on simple price action. Oscillators tend to make traders look for reversals and divergences, and when the market is trending strongly (best chances to make money), they will be repeatly entering counter-trend and losing money. By the time they come to accept that the market is trending, it will be too late to get a good entry to recoup their losses. Instead, if you were simply looking at a blank chart, it would be obvious when a market is trending, and would not be tempted by indicators to keep looking for reversals.

Common heuristics such as “buy when this line crosses this line” or “sell when this is in the overbought region” are some overly simplistic ways of using indicators. Trading in this manner does not give you any understanding about the market. It does not answer the “why” question, such as why this line crossing that line generates a buy signal. Quite often, one may also get conflicting signals from different indicators, and without an understanding of price action, one has no way of resolving the conflict.

Are indicators really needed for your decision-making?

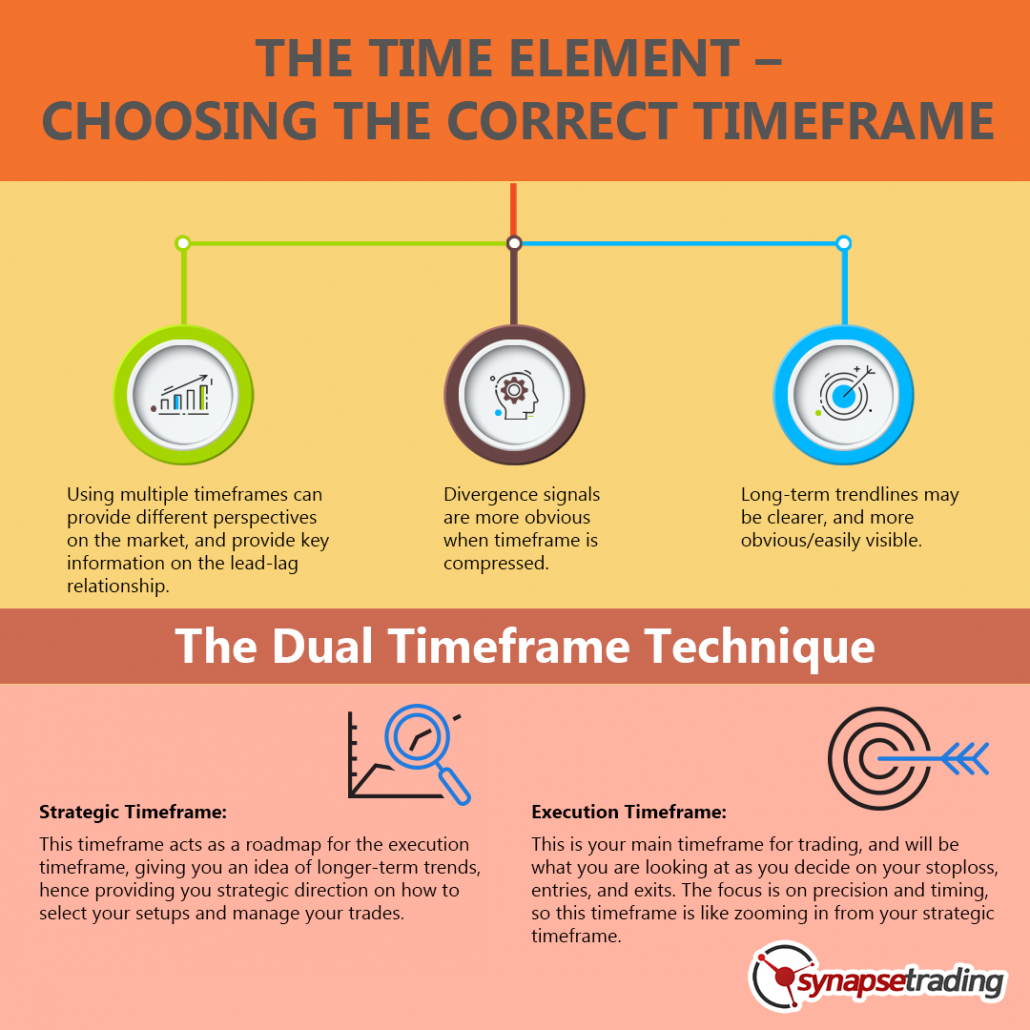

Some pundits recommend a combination of time frames, indicators, wave counting, and Fibonacci retracements and extensions, but when it comes time to place the trade, they will only do it if there is a good price action setup. Also, when they see a good price action setup, they start looking for indicators that show divergences or different time frames for moving average tests or wave counts or Fibonacci setups to confirm what is in front of them.

In reality, they are price action traders who are trading exclusively off price action but don’t feel comfortable admitting it. They are complicating their trading to the point that they certainly are missing many, many trades because their over-analysis takes too much time, and they are forced to wait for the next setup. The logic just isn’t there for making the simple so complicated.

So… Should I be using indicators at all?

The best solution for the retail investor would be to first master a firm foundation of price action and behavioral analysis, and subsequently, should he choose to use indicators, should remember that as their name suggests, they are not “entry/exit signallers”, but merely “indicators”.

Therefore, it is a matter of how you use indicators, and one should always keep in mind that indicators are there to aid you in reading the price action, and not act as a substitute for it. You can think of indicators as the training wheels of a bicycle – you will want to remove them once you learn how to ride properly.

Trading always involves uncertainty, and trying to find comfort in the certainty of indicators will lead to constant indecision, second-guessing and parameters-tweaking.

If you would like to learn how to get started in trading, also check out: “The Beginner’s Guide to Trading & Technical Analysis”