A Deeper Look at the US-China Trade War & Possible Solutions

Join our Telegram channel for more market analysis & trading tips: t.me/synapsetrading

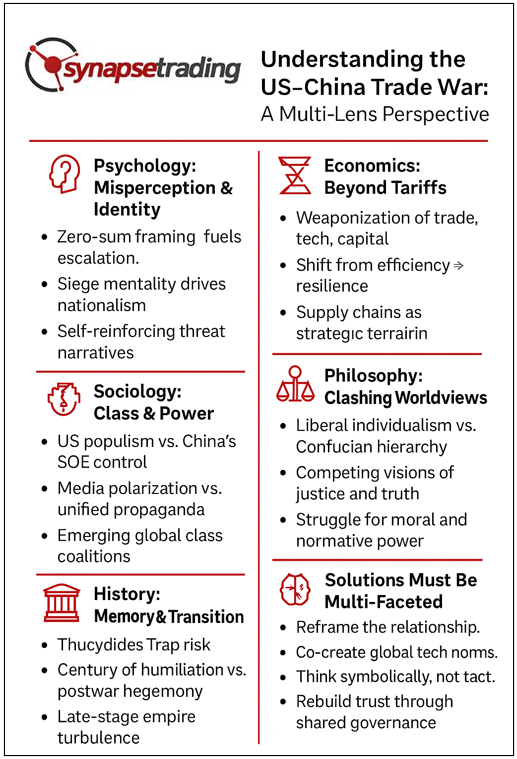

The US–China trade war is often portrayed as a clash over tariffs or manufacturing jobs. But beneath the surface lies something far more intricate — a multidimensional struggle that spans economics, psychology, sociology, philosophy, history, and complex systems. It reflects not just a rivalry between two powers, but a confrontation between competing worldviews, power structures, and visions of the future.

In this post, I explore the trade war through six interdisciplinary lenses to unpack its true impact — and more importantly, to begin shaping a multi-faceted solution that moves beyond zero-sum thinking. Because in a deeply interconnected world, the cost of misreading complexity is not just economic — it’s civilizational.

Table of Contents

1. Economics – Geo-Economic Rivalry and Structural Disruption

a. Beyond Tariffs: Economic Statecraft

The trade war marks a shift from classic trade disputes to strategic geo-economics, where economic tools are weaponized to achieve geopolitical ends. This includes:

- Export controls (e.g., semiconductors, AI chips)

- Investment restrictions (e.g., outbound capital, blacklists)

- Subsidy races (e.g., CHIPS Act vs. Made in China 2025)

It is no longer about “free trade vs. protectionism,” but about control over chokepoints in global value chains (e.g., TSMC, ASML) and securing economic sovereignty.

b. Decoupling and the Fracturing of Global Capital

China is engineering dual circulation (内循环 + 外循环), reducing reliance on Western export markets and technology. The US, in turn, is promoting “friendshoring” and reshoring, especially in critical industries like biotech, defense, and chips.

This transforms globalization’s logic from efficiency to resilience and political alignment — a paradigm shift with massive long-term cost implications.

c. Supply Chains as Strategic Terrain

Rather than tariffs, the real battleground is the architecture of global supply chains, especially:

- Data and platform ecosystems

- Clean energy tech (EVs, solar, batteries)

- Rare earths and critical minerals

These are governed less by market logic and more by control, surveillance, and techno-industrial policy — where first-mover advantage is amplified by network effects and standard-setting power.

2. Psychology – Perception, Identity, and Miscalculation

a. Threat Perception and Cognitive Biases

- US policymakers increasingly view China through the lens of realist threat inflation (e.g., China as a revisionist power).

- Chinese elites perceive US moves as containment, reinforcing siege mentality and echoing historical humiliation narratives.

This creates a feedback loop of defensive aggression, where each side’s defensive actions are perceived as offensive escalation by the other — classic in conflict psychology.

b. Leadership Psychology

- Trump’s framing of bilateral trade as a zero-sum deal and his aggressive, confrontational style polarized positions and heightened misperceptions.

- Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power, elevation of nationalism, and ideological tightening have made policy more rigid and sensitive to perceived loss of face.

Both leaders anchored the dispute in their personal and national identities, making de-escalation politically costly.

c. Collective Cognitive Dissonance

Populations in both countries experience cognitive dissonance: Chinese citizens struggle to reconcile economic openness with nationalism; Americans feel betrayed by a system that exported their jobs and empowered a strategic rival.

This manifests in:

- Scapegoating behavior

- Black-and-white moral reasoning

- Suppression of nuance in public discourse

3. Sociology – Power Structures, Class, and Social Reproduction

a. Class Dimensions of Trade Conflict

- In the US, working-class discontent (driven by deindustrialization and wage stagnation) helped fuel Trump’s election and support for tariffs.

- In China, state-managed capitalism shielded SOEs and elite firms, but rural and migrant workers bore the brunt of retaliatory job losses.

The trade war, therefore, reflects underlying social contract tensions within both systems:

- The US faces populist backlash against global capitalism.

- China navigates legitimacy through growth amid demographic and employment pressures.

b. Institutional Mediation and Propaganda

- US institutions (Congress, media, think tanks) tend to fragment and politicize narratives, reducing coherent long-term strategy.

- China’s centralized structure allows unified messaging, but limits policy flexibility due to internal surveillance and political conformity.

Propaganda plays different roles: in the US as ideological polarization, in China as state-driven cohesion.

c. Norm Shifts and New Coalitions

We’re witnessing new global social alignments:

- Global South alignment with China (e.g., Belt & Road, BRICS+)

- Western re-industrialization coalitions (e.g., EU–US on chips)

This reflects a reorganization of global class structures along civilizational and technological lines.

4. Philosophy – Worldviews, Ethics, and Ontology of Power

a. Ontological Conflict: What is the Good Life?

The trade war is a surface expression of deeper value conflicts:

- US worldview: liberal individualism, market rule of law, open innovation.

- Chinese worldview: Confucian statist meritocracy, stability through hierarchy, techno-political unity.

This reflects not just policy divergence, but ontological divergence — what constitutes legitimacy, truth, and a well-functioning society.

b. Justice and Moral Economy

- Is the protection of domestic workers a moral duty, even at the cost of global efficiency?

- Can economic development under authoritarian regimes be morally legitimate, if it lifts millions from poverty?

Both sides use moral rhetoric, but often conceal underlying power interests.

c. Foucault and Soft Power Discipline

The trade war is not just about physical goods, but also norm production — who gets to define:

- Intellectual property rights

- Cybersecurity standards

- Human rights benchmarks

The conflict reflects a deeper battle over normative power and the global epistemic order, echoing Foucault’s view that power is exerted through the definition of truth itself.

5. History – Cycles, Memory, and Hegemonic Transition

a. Thucydides Trap: Myth or Pattern?

The idea that rising powers inevitably clash with established powers (Graham Allison’s “Thucydides Trap”) is widely cited — but risks self-fulfilling prophecy if not critically examined.

Historical transitions (UK–US, US–USSR, Sparta–Athens) show:

- Power transitions need not lead to war, but mismanaged perception and rigid alliances increase danger.

b. The Century of Humiliation and Postwar Hegemony

- China’s trauma from Western imperialism (1839–1949) drives its resentment of Western-led order.

- The US, architect of post-WWII institutions (Bretton Woods, WTO), sees challenges to these as threats to global stability and moral leadership.

Historical memory shapes policy in deeply emotional ways.

c. Empire Decline and Peripheral Turbulence

As US hegemonic power wanes, peripheral regions (e.g., Taiwan, South China Sea, Central Asia) become flashpoints, echoing late-stage empire patterns (e.g., British Empire’s post-war unraveling).

History does not repeat, but it rhymes in patterns of decline, overreach, and backlash.

6. Systems Thinking – Complexity, Feedback Loops, and Emergence

a. Decoupling as Systemic Rewiring

The global economy is being restructured into semi-independent spheres:

- US-led: democratic allies, IP-centric, dollar-based.

- China-led: resource-rich partners, infrastructure-based, digital yuan experiments.

Decoupling isn’t total — but partial decoupling creates:

- Systemic duplication (two 5G standards, two payment rails)

- Higher transaction costs

- Increased fragility at the intersystem interfaces

b. Second- and Third-Order Effects

First-order effects (tariffs) are easy to see. But second- and third-order effects include:

- Techno-nationalism escalation → arms race in quantum, biotech

- Climate cooperation breakdown → higher planetary risk

- Global South re-alignment → new geopolitical fault lines

Small shifts in leverage points (e.g., banning one chip type) can cascade through multiple systems — financial, environmental, diplomatic.

c. Meta-Crisis and Bifurcation

We may be entering a meta-crisis zone, where multiple systemic stressors (trade, climate, AI risk, demographic aging) interact and create phase shifts.

Systems analysis suggests:

- Leverage lies in norms, trust, and shared governance models

- Emergence of a new order is more likely than restoration of the old

Is there Any Solution to This?

The US–China trade war is not merely a dispute over trade deficits or national pride. It is a crucible where our deepest assumptions about progress, power, and prosperity are being tested. As we peel back the layers, we begin to see how economic decisions ripple into psychological narratives, how sociopolitical tensions reinforce historical traumas, and how the global systems we inhabit can either spiral toward fragmentation — or be reimagined into something more cooperative and resilient.

This is not just a geopolitical standoff; it is a moment of systemic reckoning. Beneath the tariffs and tech bans lies a larger question:

Can two fundamentally different civilizations find a way to coexist, compete, and collaborate in a multipolar world without collapsing into mutual destruction?

A meaningful path forward demands more than reactive policy or zero-sum logic. It requires cognitive flexibility, moral imagination, and a renewed commitment to shared norms. No single discipline — whether economics, international relations, or security — can untangle this web alone. But integrated thinking across lenses offers fertile ground for solutions.

Multi-Faceted Solutions

Any long-lasting solution has to be multi-facted in nature, and take into consideration various perspectives. Here are some possibilities:

- Economic Realignment with Safeguards:

Develop bilateral and multilateral mechanisms that allow selective decoupling in sensitive sectors (e.g., defense, critical tech) while preserving interdependence in global commons (e.g., climate, public health, financial stability). This balances national security with global cooperation. - Norm-Based Tech Governance:

Create transnational frameworks for tech standards, AI safety, cybersecurity, and intellectual property rights — not controlled by one bloc, but co-designed by a coalition of stakeholders including the Global South. This prevents techno-colonialism while allowing ethical innovation. - Psychological De-escalation through Narrative Shifts:

Encourage a shift in political and media narratives from confrontation to constructive competition. Mutual acknowledgment of grievances (e.g., historical trauma, economic dislocation) can foster empathy and reduce zero-sum threat perception. - Institutional Reform for Resilience:

Support global institutions (e.g., WTO, IMF, UN bodies) to evolve beyond post-WWII structures, incorporating new voices and adapting to decentralized power dynamics. Trust must be rebuilt through transparency, inclusivity, and enforcement mechanisms that work. - Civilizational Dialogue, Not Just Diplomacy:

Establish cultural and academic exchanges that deepen understanding of divergent worldviews — liberal individualism vs. collectivist meritocracy, Western vs. Eastern ethics. Such ontological dialogue may open imaginative possibilities where policy has stalled. - Systems-Level Risk Mitigation:

Recognize the meta-crisis of overlapping fragilities — climate change, aging populations, tech disruption, inequality — and treat the trade war as one expression of broader systemic stress. Cross-sector coordination and anticipatory governance are key.

Concluding Thoughts

If we fail to take a multi-dimensional approach, we risk entrenching the very divisions we seek to overcome. But if we engage across disciplines, histories, and cultures — not to impose dominance, but to negotiate coexistence — then the trade war may yet be transformed from a symbol of breakdown into a catalyst for renewal.

To reflect further, consider:

- What would a “win-win” outcome look like in a world where both powers define success so differently?

- Are we building economic systems to serve people — or asking people to serve systems?

- If the next global order emerges from this conflict, what values do we want it to be built upon?

Let me know your answers in the comments below!

Our flagship mentoring program is suitable for both beginners and advanced traders, covering the 4 strategies which I used over the past 15 years to build up my 7-figure personal trading portfolio.

Our flagship mentoring program is suitable for both beginners and advanced traders, covering the 4 strategies which I used over the past 15 years to build up my 7-figure personal trading portfolio.

If you're looking for a reputable brokerage that covers all products (SG stocks, US stocks, global stocks, bonds, ETFs, REITs, forex, futures, crypto) and has one of the lowest commissions, this is what I currently use.

If you're looking for a reputable brokerage that covers all products (SG stocks, US stocks, global stocks, bonds, ETFs, REITs, forex, futures, crypto) and has one of the lowest commissions, this is what I currently use.

After trading for 18 years, reading 1500+ books, and mentoring 1000+ traders, I specialise in helping people improve their trading results, by using tested trading strategies, and making better decisions via decision science.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!